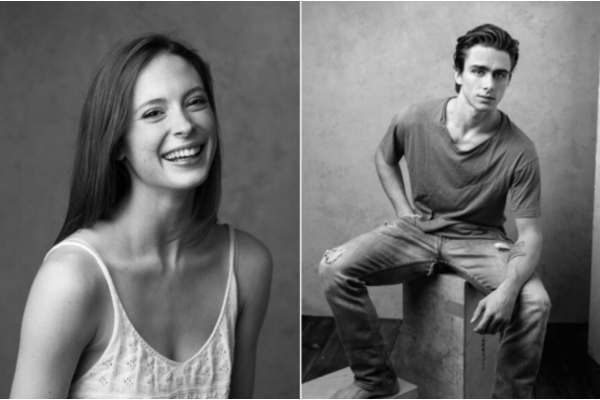

Photo credit: Karolina Kuras

Francesco Gabriele Frola and Emma Hawes ‘in conversation’ with Lyndsey Winship

14th April 2022

Francesco Gabriele Frola (‘Gabriele’), at 29, is a Lead Principal with English National Ballet (ENB). Italian by birth, he came to London via Germany, Mexico and Canada. Emma Hawes, at 28, is a newly promoted Principal with the same company. Born in Delaware, USA, her journey to London was via Canada. Their different backgrounds and approaches to dance were explored ‘in conversation’ with Guardian dance writer Lyndsey Winship.

The Chair of the London Ballet Circle, Susan Dalgetty-Ezra, welcomed the two dancers and thanked them for agreeing to the interviews.

Lyndsey commenced the conversation by asking the dancers how they found life in London.

Emma said she had arrived at an ‘interesting moment’. For her it had been a big jump, leaving a comparatively comfortable situation in Canada for something completely new. It was time to expand her horizons and try something ‘a bit scary’. And then restrictions due to the pandemic had come into force before she had really discovered London.

For Gabriele the move to London had involved more than just a new company; he felt it was time to come back closer to his family – not that Covid had made that easy!

As to the reason they had joined ENB, Emma explained that she had been intrigued by the style of the company and had watched many video clips. Maybe the first thing she had noticed was Akram Khan’s Giselle. She loved the work of Tamara Rojo and Alina Cojocaru. Gabriele agreed that Tamara’s influence on the ENB was considerable and had been significant in his wish to join the company. His immediate background had involved a lot of Cuban styles of dance; he wanted to improve his techniques and try something completely new.

But, said Lyndsey, Tamara is now moving on. Gabriele felt that she was leaving the company in its best possible state, with a wealth of talented young dancers. Emma agreed; everyone continually needs to learn and it was good to be pushed by younger members of the company.

Lyndsey went on to explore the backgrounds of the two dancers.

Both of Gabriele’s parents had been dancers who had opened a school in Parma, in northern Italy, which was where he first studied. He considered that his parents had been quite tough on him, not allowing him license because he was their son. Parental influence ensured that he was immersed in ballet from a very early age. However, he had a keen interest in football, which is what he wanted to pursue. At around the age of fifteen he had to make the choice to continue dancing or try to develop his footballing skills. He conceded that deciding to study ballet could be difficult for a male; however, he wanted to build on the foundation laid down by his parents.

Emma also had a sporty background. She enjoyed swimming, in which she had been an active competitor alongside her dance classes. It had often been difficult to find the right balance between the two activities; she felt that this had given her important skills in learning how to balance priorities. At about eleven she was offered a place at the Canadian National Ballet School. She confessed that she had some trepidation because of not quite knowing what she was getting into, but once she settled in she really loved her time there. A close relationship existed between the School and the National Ballet and at seventeen she was accepted into the company.

When questioned as to how many of her school contemporaries had also been offered places in the company, Emma thought three out of a class of around twenty-one. The competition was tough, and Lyndsey thought that Emma’s potential had already been spotted.

Emma described the Canadian company as ‘cool’. She was dancing with people she had admired when a student. There were long rehearsal periods and the quality of the work was amazing. However, the corollary of extended rehearsal was rather short show periods, so that time on stage was perhaps more limited than she would have liked. In that respect ENB had proved to be different. There were more shows, and sometimes roles had to be developed and refined on stage as well as in the studio.

Gabriele then described the next stages in his career. At about fifteen he had moved to John Neumeier’s School of the Hamburg Ballet. Germany was a great country to live in, where the ‘rules’ were important. He felt that he was growing as a person and that he was able to refine his technique and clean up his steps.

From Hamburg he moved to Fomento Artistico Cordobés in Mexico where he came under the influence of Cuban dance teachers. Gabriele was an enormous admirer of Carlos Acosta. The dancing was more bravura and he learned more ‘tricks’. His teachers put pressure on him to practise more jumps and turns; in fact, with hindsight he wondered whether it had been right to pressure students so much. Class was supremely important; you went on repeating techniques until they were perfect.

Lyndsey was interested to hear about the role of Nijinsky, which Gabriele had danced in both Canada and Paris. How difficult had it been to take on the role of an individual who was probably the world’s best known male dancer?

Gabriele explained that he had originally been cast in a different role in John Neumeier’s ballet, but that he had rehearsed the title role and then danced it. He had danced a solo from this ballet at the Prix de Lausanne, where he had been a semi-finalist. He had researched Nijinsky’s life and times, for instance by reading his diary. Nijinsky clearly had mental problems, but Gabriele believed that fundamentally he was a nice person. Gabriele also believed that Nijinsky was ahead of his time, for instance he was famous for his jumps and turns, quite unlike his contemporaries. Gabriele had danced the part a number of times; each time he felt he understood the man better and thus given a better interpretation of the role.

Lyndsey wondered whether Emma had danced any particular roles of note in Canada?

“Swan Lake” replied Emma. The principal coach, with a Vaganova background, had taken a very different approach to the role, especially of the white swan. For instance, arm actions were intended to emulate wings rather than the movement of water, and had to appear more muscular. She had personally found it quite a challenge to ‘find’ Odette.

A clip of Emma’s solo in the ENB production of Raymonda was then shown. For this ballet Tamara Rojo had reimagined the story to give it a contemporary sensibility while retaining the original Petipa choreography. Emma described the preparation and rehearsal for this new production as being very different from normal because of the pandemic and the social distancing restrictions it necessitated. However, she considered the constraints actually assisted the development of the ballet as they allowed the individual dancers rather more opportunity to develop their own steps.

Tamara had spent much time discussing how her version of the story fitted the choreography. At one point they had even done a Turkish dance workshop; hard but fun. Emma considered it valuable to re-evaluate old stories. It had also been possible to give more ‘substance’ to the female roles.

Lyndsey went on to ask about working with the choreographer William Forsythe. William’s choreography was rigorous, involving a great deal of repetition. The dancers all worked as a great team with enormous energy. His work was very physical but the dancers all related well to him; he knew how to make them respond.

Emma spoke about Blake Works 1, a clip of which was shown. She explained that the choreography necessitated a degree of risk taking, for instance by deliberately going off balance. This was choreography taken to its limits!

Gabriele commented that William wanted the dancers to give 100% in every step. Often they were classical steps but performed in a fresh, new way, using pop and dance music, and it was great fun to do. It was an interesting way to develop classical ballet and make it more attractive to today’s audience. Lyndsey wondered whether ballet needed to change to remain relevant. Both dancers agreed on the need to attract audiences who would not normally consider watching a ballet.

A clip of Diana and Actaeon was then shown, in which Gabriele demonstrated some of his fantastic jumps and turns. This pas de deux (with Natalia de Froberville) had been part of the Ukrainian Ballet Gala held at Sadlers Wells in September 2021. Both dancers had performed in the subsequent Dance for Ukraine gala organised at the Coliseum by Ivan Putrov and Alina Cojocaru. This had been a terrific event; they were delighted to have met and worked with so many others, and to have raised money for Ukraine.

Lyndsey asked how much they saw ballet as an international art form. Did it affect their views on borders and differences? Emma replied that she had come from a relatively small town. She was immensely grateful that her involvement in ballet had taught her so much about the world. Gabriele agreed that living in different countries had allowed him to grow considerably as an artist and as a person.

Were there any roles that either Gabriele or Emma longed to dance?

“So much” said Emma. Work from new choreographers; it was exciting to keep taking risks. Gabriele would like to dance Don Quixote, and more Macmillan works. He would also like to tackle the role of Nijinsky again, as he felt that he now understood the man even better.

Some questions from the LBC audience were then posed to the dancers.

In answer to a question, Gabriele said that recreating the Nijinsky role in Paris was extremely special because Nijinsky himself had performed at the same theatre, including, of course, the first performance of Rite of Spring which caused such a riot.

Emma was asked whether the off-balance elements of Balanchine works which she had danced in Canada had assisted her in preparation for the Forsythe ballet, and she agreed that it had.

Gabriele was asked about his many tattoos. He explained they all had symbolism, for instance to do with his family – although they had to be covered up, usually with make-up, during performances.

He was then asked about dancing with Alina Cojocaru in Marguerite and Armand, which he agreed was a very special experience. She was excellent to dance with; always clear exactly what she wanted to do, and artistically brilliant. He had also danced it in Canada at around the same time.

Both dancers were asked about participation in competitions. Emma has always been wary and had only ever taken part in one, the Erik Bruhn Prize. However, she had somewhat changed her mind because she could see that competitions provided a show case for young talent.

Gabriele had taken part in many competitions, regarding them as a fun part of ballet. He felt they were important, not necessarily to win but because they provided young dancers with opportunities to actually appear on stage in front of an audience.

They were asked about the new ENB season, just announced. The Mats Ek work should be particularly exciting. It is important to have choreographers creating in the studio; Tamara had been great at promoting this. It would also be good to be touring once again.

Finally, Lyndsey asked what dance meant to them, and how they felt just before a performance.

Gabriele was not usually nervous; instead he was excited. For him dance had many meanings, which changed with time. He considered dance to be his therapist. He could express himself, talk without speaking and listen to himself quietly.

Emma told us that she was quite shy and didn’t really like being watched, which was strange for someone whose life existed on stage. She often felt nervous before a performance, but deep breaths and friendly colleagues always helped. Dance itself connected her with the audience, which was great.

They ended by expressing approval that ballet itself was becoming more diverse and companies less hierarchical and more friendly. All of which would hopefully attract new audiences.

Gabriele and Emma were thanked profusely by Susan Dalgetty-Ezra.

Written by Trevor Rothwell. Edited/approved by Francesco Gabriele Frola, Emma Hawes and Lyndsey Winship.

© Copyright LBC