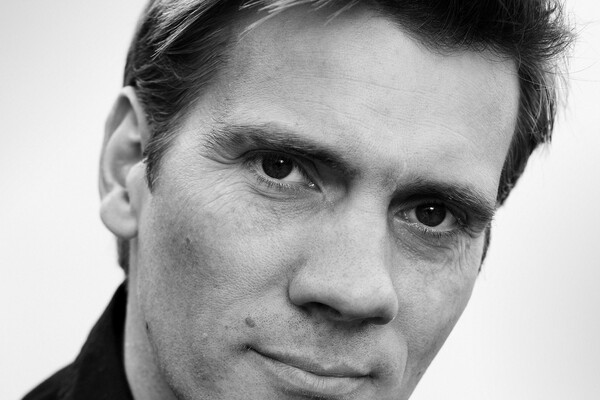

ADAM COOPER, DANCER, MUSICAL STAR, CHOREOGRAPHER AND PRODUCER “IN CONVERSATION” with Gerald Dowler

9th December 2020 via Zoom

Gerald Dowler began by explaining that Adam was in Munich, where he was rehearsing an operetta at the Staatstheater am Gärtnerplatz. He explained that the production he was working on, an operetta called Der Vetter aus Dingsda, would be livestreamed rather than presented to a live audience, although they had rehearsed on stage and with an orchestra – but they would be “doing it on stage to an empty house.” He also explained that he had “branched out into choreography” after leaving the Royal Ballet, and that was why he was working on an operetta, and in Germany.

“Choreography has become almost as much, or sometimes more, than my dancing career. It has taken me through ballet, contemporary, into musical theatre quite early on. That then led on to doing a musical in Germany, and I was then invited back to choreograph an operetta and more musicals, including directing one. The opportunities here have been fantastic for my career and I’m very grateful.” He explained that funding for the state theatres in Germany is particularly good and he has done 2 to 3 productions there every season for the last five years. “They’re always doing new productions and always looking for new people. It’s only Munich so I can get back at weekends to see the family”, although, during the pandemic, he had had to stay in Munich to avoid quarantine.

Gerald then asked how choreography became part of Adam’s life, and he explained this had been the case since childhood: “I was making up dances when I was 7 or 8 years old with my brother.” He went to the Royal Ballet School at the age of 16. “I won the Ursula Moreton competition… and that really fired up the choreographic side of me.” Despite David Drew’s requests, Adam was not able to develop this work while he was dancing. The opportunity came when he left the Royal Ballet and he could begin to choreograph at London Studio Centre and with Scottish Ballet. He had now developed relationships with a whole range of companies, and being involved in the creative process with Matthew Bourne was instrumental in developing this area. Adam explained that he told his agent he wanted to try performing in musical theatre “and she got me a lead in a musical, On Your Toes, and the choreography at the same time. That was a big ask.”

The discussion then covered the ways in which Adam’s dancing career may have influenced his choreography. Adam explained that a mixture of styles and all the approaches he experienced from different choreographers were part of his learning. “I’ve never lost the urge to do it, and working with those great choreographers encouraged me even more.” Asked about choreographers whose work he did not feel sympathetic to, Adam did admit there had been occasional cases of this. “Luckily enough, I haven’t been asked to do much terrible choreography. You want to be professional and do the best you can. The one joy about being a freelancer is that you can say no to things.”

His first commission, Rodgers and Hart’s On Your Toes, was seen in Leicester and then at the Royal Festival Hall and in Japan. “It’s a wonderful musical about an American jazz hoofer mixing up with a Russian ballet company, and he ends up playing the lead part in the ballet at the end.” Irek Mukhamedov played the Russian ballet dancer and Sarah Wildor, Adam’s wife, played opposite him. He explained that he had had to work on a range of styles including jazz, and tap which he hadn’t done since he was 16. “It was a baptism of fire, definitely, but it worked out really well.”

Gerald then asked how working with Matthew Bourne changed Adam’s work. He explained that Matthew involved him in the storytelling, first in Swan Lake but particularly with Cinderella, and that helped his creativity and coming up with movements – and it led to him becoming more well-known and being offered other work. “It was great for me on lots of levels, I really look back fondly on that period.”

How, though, did the Swan Lake opportunity come about? Adam explained that he had met Matthew after seeing Highland Fling, and he said he had seen Adam in many Opera House performances. “He was definitely looking for someone outside his own world.” It was a few months later that he got the call asking if he would like to be a male swan in Swan Lake. Despite his uncertainty about how it might work, Adam realised this might be his only chance to be the lead in a new ballet, which would not have been possible at the Opera House. “It felt like a huge risk, but I’m not afraid of taking a risk, I thought let’s go for it. People were damning it before we had even taken a step in the studio. I knew it would be a lovely experience to just try.” A lot of the Swan material came from an early workshop featuring Adam with his alternate David Hughes and Scott Ambler as the Prince: “That was how that style came about; David and I worked on Acts 2 and 4 while the company were working on Act 1.”

Adam danced the Swan from 1995 to 2003, sometimes fitting in performances between Royal Ballet appearances: “That was the only way they would let me go.” During the Piccadilly Theatre season he was combining the two and got injured; he also danced in the Dominion Theatre season and in Japan. He went back to the production for the first time two years ago to rehearse the swans. “Two things struck me: that I was incredibly proud of what we had done and that it had changed a lot. It was quite a challenge.” He also found the musicality was different. “And it’s been through a lot of swans.” All the new Swans, he found, were bringing something of themselves to it “which is the sign of a good role.”

How important, then, is musicality in Adam’s work? “For me it’s key, I always start with the music. The music channels me and tells me what to do. It’s my ballet background from when I was doing principal roles, musicality is everything. There is joy when movement and music come together. What separates good dancers from great dancers for me is how they interpret the music.” He illustrated this by his memories of Lesley Collier in Requiem. Asked about whether he found some types of music difficult to choreograph, he did acknowledge that sometimes there are particular challenges, for example when working on the Kinks musical Sunny Afternoon. “I try to find nuances for myself in it, that’s the challenge. But I do that when I’m using a piece of classical music as well. And I’ve enjoyed choreographing for jazz music too. If I’m doing a piece of dance, I’ve picked the music; if it’s a musical and I’m not inspired by the material, I don’t do it.”

The discussion then moved on to the relationship with the performers in a musical or operetta. Adam explained that he had always been lucky with the people he had worked with, and “getting them on side with the reason why you’re doing it the way you are.” After 8 or 10 shows in Munich, he knows the company very well; and asked about his ways of working, Adam did agree he is a choreographer who demonstrates. “If I’m doing a musical or an operetta I go in very well prepared and show it to them, with an assistant to help me. If it’s pure dance I don’t do that, I like to work on a body and see what a body can do, for me that is the most satisfying way of working. Although you need a clear idea of how it will work, and everybody needs to feel they are part of that creation.”

Asked to discuss highlights from his time at the Royal Ballet, Adam found it difficult to choose although he did mention working with William Forsythe and Sylvie Guillem in Herman Schmerman and then Firstext “which I think they only did in one run. One of the other memories that I cherish was Rudolf in Mayerling, the Everest of male ballet roles.” He also mentioned as a highlight dancing all his first principal roles with Darcey Bussell, including Prince of the Pagodas, and being in Macmillan’s last three ballets: “Macmillan was always very encouraging.” Adam spoke in particular about the creative process when working on The Judas Tree. “He obviously saw something in me and gave me leading roles. He really used his dancers’ talents and their strengths.” Adam gave an example of this as the differences between the Kings in Prince of the Pagodas. Some of these pieces divided audiences however, and it was dancing in The Judas Tree that led to Adam’s only experience of being booed off a stage: “Judas Tree was a step too far for Germany when I performed it there with Leanne Benjamin.” Summing up his experience of working on those ballets Adam said “What I loved about Macmillan was that he had an idea but he wanted me to create it, and that was really lovely.”

Adam still performs because “I still get a buzz out of it – and people keep asking me!” He explained that he loves connecting with an audience. He misses it when he’s not performing but he is usually being creative in other ways then. “The relationship between a performer and an audience is a unique one; you appreciate what an audience likes and doesn’t like every time you step on stage.” He also explained how he learns from watching performances, when he has a chance to do so.

Moving on to questions from the audience. Gerald asked how Adam chose music to choreograph to. He explained that he looks for something with a structure and which inspires him “or gives me goose-bumps. But you also have to be able to rise to it; I always try to find something I can match. If you’re going to use a great piece of music like Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet, you have to be able to match it. You have to be able to step into a room and say this is what we’re doing, trust in me, go with me.”

Gerald then asked Adam how much he changes work that has already been created and is being performed again. He explained that dance may usually stay the same but he has had the experience of revisiting musicals and tweaking things. “It’s always ongoing. I always think I can do better than that; my tastes change in my work all the time.”

The next questioner asked how much pressure was involved in Adam dancing with his wife Sarah Wildor in Cinderella. They had not danced together romantically with the Royal Ballet. “In a way there is more pressure because you do have to go home with that person and it can be a tricky evening if things haven’t gone to plan, but luckily, mostly it did.” They were doing 4 to 5 shows a week in London and in Los Angeles but “it was a joy to be in that environment with her, she lives it every night.” Later he got the chance to choreograph on her as well, in On Your Toes and Les Liaisons Dangereuses, and “she is one of the most musical dancers I know.”

Of the shows Adam had worked on, the highlights included Les Liaisons Dangereuses, which he worked on for 6 years before it appeared, after working with the composer and designer as well as the crew. It opened in Tokyo, Japan to “a feeling of relief and a sense of achievement, as I was lying on the floor at the end of the sword fight on the opening night.” Although Adam had multiple roles on the production he also had several assistants in each of the areas, including his wife and his brother (who was in the second cast). “It’s all told through letters but I didn’t want spoken text, I wanted to do it all in dance. I relish those opportunities.” When working, as he is now on Der Vetter aus Dingsda, an operetta from 1918, Adam says he treats the piece like a musical but being true to its time, for example on that production which is now set in the 1960s. The production was being livestreamed on 17th December 2020 - information and images: https://www.gaertnerplatztheater.de/en/produktionen/der-vetter-aus-dingsda.html

The next questioner asked whether Adam’s children were interested in dance? “The quick answer is one yes (his daughter), but the other (his son) no. They both like singing and acting. Sarah and I talked about that a lot and whether we should encourage them or not.” Adam was then asked whether there was any role (dancing or acting) he would like to take or to have danced? He said he would love to have danced Antony Dowell’s role in A Month in the Country. “I was always a massive Ashton fan. The casting would go up year after year and I wouldn’t be anywhere near it. I loved the story and the music for his solo as Beliaev, it was modern romantic ballet at its best. I loved the beautiful cleanliness of the choreography. One year I plucked up the courage to say I would love to learn the role.” He was allowed to learn it but he never performed it. Where acting roles are concerned, he explained it’s difficult to say, although he would like to be in Shakespeare, perhaps Tybalt. Does he feel he was typecast when he was in the Royal Ballet? “I always thought that I could play anything, and that there was more that I could have done. I did feel slightly typecast as I would play the villain quite a lot, not often the romantic lead although I was begrudgingly given Romeo and I did Swan Lake. I was known as part of the modern dance bunch. That was my thing, the villain or the contemporary one.”

Adam was then asked what happened to the proposed Michael Clark piece for a Royal Ballet triple bill. He explained that “at the company time is everything and in those days if somebody didn’t slot in it wouldn’t work. It got pulled about two weeks before it was due to go on stage as there was a realisation that it was never going to get finished. But we all loved what we were doing in the studio.”

And his most embarrassing moment on stage? “Well dropping Sylvie Guillem mid-performance in Herman Schmerman was an embarrassing moment, but she smiled as it was her fault not mine. I also split my trousers in Act III of Swan Lake but it was at a dress rehearsal.” He has also performed Singing in the Rain more than 700 times but remembers how well he got on with the original co-stars in the cast at Chichester and London. In one performance, after singing Good Morning, they were completely out of breath and they simply could not stop laughing – but luckily the audience joined in “with the whole theatre in hysterics for a minute and a half.” As Gerald said when summing up, “that’s the brilliance of live theatre.”

Adam Cooper hopes to be playing in Singing in the Rain at Sadler’s Wells from July to September 2021 before taking it to Japan. With that, Susan thanked Adam and Gerald and said she already had her tickets.

Written by Chris Abbott; edited/approved by Adam Cooper and Gerald Dowler

© The LBC 2020